Do We Have to Waste Half the Votes?

As we shared with you in our last message, we’ve now submitted all our written arguments for the upcoming Charter Challenge court hearing (Sep 25-27 in Toronto). We’re currently waiting to receive the government’s written argument and are now working on our oral arguments.

In the meantime, we wanted to share with you a few more details from Fair Voting BC’s affidavit, which presents some insightful metrics we’re using to reinforce a number of our key arguments.

In a previous message, we reported that over half the voters in the 2019 election cast “wasted votes” (votes that didn’t help elect an MP). While this was true in that election, the court will want to know if this is a consistent pattern across time, and if changing the voting system will likely change this.

To answer this question, we defined a Representation Metric that could be calculated both for countries such as Canada that use the First Past the Post voting system and for countries that use proportional voting.

More Than Half the Votes Are Wasted in Canadian Elections

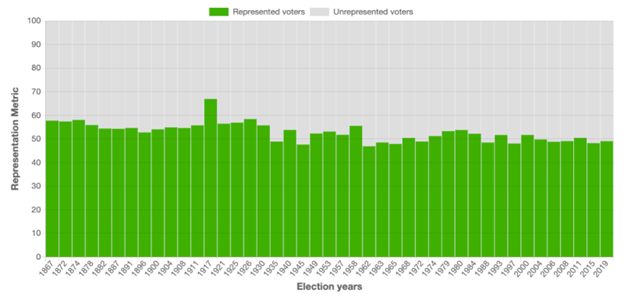

In Canada, the Representation Metric is simply the proportion of voters who cast a vote for an elected candidate. Thanks to work by Byron Weber Becker (University of Waterloo), we were able to show that for nearly the past hundred years (since 1935) the Representation Metric has averaged less than 50% over the past 40 years.

Representation Metric for all federal elections in Canada since Confederation. The Representation Metric expresses the percentage of voters who have voted for an elected MP. Since 1984, the Representation Metric has averaged just 49.8%.

Are As Many Votes Wasted Under Proportional Voting?

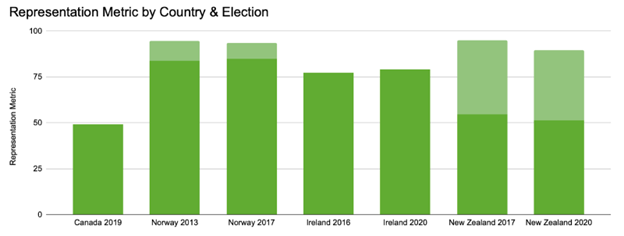

Absolutely not. In Proportional Representation (PR) voting systems, the Representation Metric is typically much higher (and the “wasted votes” much lower), because far higher proportions of the ballots cast affect the resulting makeup of the legislature. To demonstrate this point, we analyzed the results of recent elections in three countries using different types of PR systems (Norway (List PR), New Zealand (MMP), and Ireland (STV)). Under all three of these systems, the Representation Metric would have been far higher, ranging from about 77-79% under Ireland’s ‘direct representation’ STV system up to as high as 94-95% under Norway’s List Proportional Representation system.

Representation Metrics for Canada (2019 federal election) and two recent elections in each of three selected countries using proportional voting (to demonstrate consistency of findings). The darker shade represents those voters who are represented by a representative for whom they have explicitly voted (‘direct’ representation), while the lighter shade represents those voters who are represented by a representative who won a seat by virtue of votes cast for the representative’s party (‘indirect’ representation).

This evidence is critical for us to make the points that (1) our recent experience in Canada is not an anomaly, but rather a routine and expected outcome of elections under FPTP, and (2) any number of alternative voting systems would markedly increase the proportion of represented voters.

Charter Challenge In the News

The Charter Challenge is in the news! Maxwell Cameron, a professor in the Department of Political Science and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia, contributed an opinion piece to The Globe and Mail titled “The Charter challenge of first-past-the-post could lead to a better electoral system.” To read the piece, click here.

Thank you so much for your continued support. More details shortly!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Charter Challenge Update - In Court Next Month!

Our date in court is approaching rapidly and there is important and exciting work underway.

The Charter Challenge for Fair Voting will be heard in the Ontario Superior Court in Toronto next month (Sep 25-27). The hearings will be open to the public, and we’ll send you all the details as soon as we have them confirmed.

In the meantime, here’s an update on the work over the past month and a half. At the end of June, we told you that, thanks to your generous support, we had reached the very significant milestone of having submitted our factum (the written argument for the case).

Since then, four external organizations have submitted supplementary arguments of their own (called interventions) - three supporting our case, and one arguing against.

-

Fair Vote Canada submitted a review of electoral reform attempts throughout Canadian history, clearly demonstrating that previous efforts were thwarted by partisan self-interest and urging the court to act to defend voters’ democratic rights.

-

The UK-based Electoral Reform Society reinforced many of our core arguments, and noted that the issues we identified play out with similar effects in the UK.

-

Apathy is Boring is a Canadian advocacy organization seeking to improve engagement and participation of youth in our democracy. Their submission argues that our current voting system creates a number of significant barriers to participation by and representation of younger voters.

- Finally, the Canadian Constitution Foundation doesn’t directly take a position on the relative merits of different voting systems, but argues that our first-past-the-post system is “constitutionalized” and that the court cannot force the government to change it. We disagree, and our lawyer, Nicolas Rouleau, submitted a compelling and well-argued response to their submission.

What’s Next?

The federal government is expected to submit their written argument very shortly, at which point all the written documents will be released publicly. The team will read the government’s argument very carefully, and take it into account as we prepare oral arguments.

Thank you for your continued support. More to come soon!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Major Milestone! We’ve Submitted Our Factum!

We have an exciting update on the Charter Challenge for Fair Voting. On June 16th, we submitted our factum - the written argument of our case provided to the courts in advance of the hearing in September 2023.

This important work followed our cross-examination of government witnesses over the winter and spring months. We are making tremendous progress on the case - none of which would be possible without the generous support of our Charter Challenge donors.

Through our evidence package and factum we have produced strong evidence that half of eligible voters do not have effective and meaningful representation. While the factum will not be publicly available until late August, here are a few key highlights:

- This case is fundamentally about whether Canada’s highly disproportional method of translating votes into seats (“first past the post”) violates ss. 3 and 15 of the Charter, by failing to provide effective representation to all Canadian voters and by discriminating against women and minorities.

- Our case is based on the fact that Democratic theorists now agree that democracy requires more than simply voting and electing representatives. Representatives need to effectively represent voters and give them a real voice in the deliberations of parliament by actively supporting and promoting their views there .

As we know, and have illustrated in the factum, our current system results in many negative outcomes, including the significant under-representation of minority perspectives, whether in terms of political views or identity. As such, we are asking the court to strike down the current election law and have the government implement a fair replacement.

Thank you for your on-going support of the Charter Challenge - you are critical to the success of this case!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Celebrating an important fundraising milestone!

Thanks to your contributions and the support and donations of many other Charter Challenge champions, we have reached another important milestone in our fundraising efforts. We have surpassed our $30,000 goal for the drafting of the factum (our written argument of the case). This is excellent news, and sets us up for success in the coming months!

Here’s a reminder on the status of the case:

- The case was filed with the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in October 2019.

- We served the government with affidavits and an evidence package in May 2021.

- Government affidavits were received in late Fall 2022 and are currently being reviewed.

- Court date was confirmed. The case will be heard September 25 - 27, 2023.

We will have more to share next week on the government’s evidence and our current work in reviewing and preparing response evidence.

In the meantime, we’re pleased to share that we are planning a Charter Challenge donor webinar for early 2023 with the Charter Challenge team and lawyer, Nicolas Rouleau. Stay tuned for details on this exciting event!

As well, we are kicking off the next phase of fundraising which will be focused on raising $25,000 to cover the costs of presenting our case in court.

Thank you for your continued support.

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Court Date Confirmed!

We are very excited to share that the Charter Challenge now has a court date! Our case will be heard September 25 - 27, 2023 in Toronto.

This is a critical moment for the challenge, and it would not have been possible without your support and contributions!

We still have plenty of work to do prior to the hearing dates. Evidence is expected from the government very shortly, at which point we'll review it and start preparing our reply evidence. Cross-examination will be completed in March 2023, and the factum (the written argument we provide to the courts prior to the hearing) will be filed in late Spring 2023.

Thank you again for all your support in getting us to this point. More exciting updates to come very shortly!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Case Update & More Fair Voting BC Evidence

We hope you had a wonderful summer! Fall is almost here and the Charter Challenge case work will be ramping up again soon. We're pleased to share an interim update at this time and provide more details on Fair Voting BC's evidence.

Case Update

Charter Challenge lawyer, Nicolas Rouleau, has been in touch with the government. We are expecting them to file their response evidence by the end of the month. Once confirmed, we will send an update to all supporters on next steps.

At this time, we do expect the current case timeline to shift with a case hearing date in 2023. As soon as details are confirmed, we'll be in touch.

Fair Voting BC Evidence - Some Voters Are More Equal Than Others

The last two messages showed how fewer than half the voters are represented by an MP they’ve voted for and how it can take barely a quarter of the votes for a political party to win majority power.

Only a Third of Seats “In Play” in Typical Election

In the next section of the affidavit, we show that only about a third of all seats across the country are truly in play in any given election - “15% of all ridings were decided by a margin of less than 5% in 2019, and an additional 13% by a margin of under 10%. These ridings are the most likely to change hands and are commonly referred to as ‘swing’ seats or seats ‘in play’. Conversely, 32% of all ridings were decided by a margin of over 25% . These seats are considered to be relatively unlikely to change hands in a subsequent election and are commonly referred to as ‘safe’ seats.”

Histogram of margins in the 2019 federal election. Ridings where the margins are relatively low (<10%, shown in red and orange) are considered to be ‘swing’ seats, while ridings where the margins are relatively high (>20%, shown in green) are considered to be ‘safe’ seats.

Voters in Different Regions Don’t Matter Equally

This is important, because “the distribution of safe and swing seats varies across the country, affecting voters in different ways in different places,” which means that the various regions of the country don’t all matter to the same extent in an election. In general, the outcome in races in BC are most uncertain, while those in the Prairies are essentially pre-ordained, and because the outcome in each riding is “all or nothing”, this means that the overall election results are highly sensitive to small changes in local conditions. In effect, some voters are more “equal” (or influential) than others, which violates the democratic principle that voters should matter equally, no matter where in the country they live.

This dynamic is the root of the well-known disproportional and occasionally highly counterintuitive election results produced by the FPTP voting system (e.g., in the 2019 election where Conservative Party candidates received 1.2% more of the vote than Liberal Party candidates, but were elected in 36 fewer ridings).

Coming up in our next message - an overview of our “Parity in Legislative Power” project in which we “analyze, quantify, and visualize existing distortions created by the Canadian electoral system in relation to the principle of “one person, one vote”, i.e., distortions in the “relative parity of voting power” of Canadian citizens.”

More to come soon!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

“Majorities” Aren’t Really Majorities

In our last post, we introduced you to the first pieces of evidence laid out in the affidavit written by Antony Hodgson (president of Fair Voting BC), in collaboration with Byron Weber Becker (University of Waterloo) and Fred Cutler (University of British Columbia), about the results of the 2019 federal election and described our key evidence that fewer than half the voters ended up voting for an elected MP (crucial for our argument that half the voters are not effectively represented).

Government MPs Typically Represent Only a Quarter of Voters

After that, our affidavit makes the additional point that, “regardless of whether a government is a majority or a minority, the MPs elected to the governing party are routinely elected by only a small minority of voters” - typically less than a quarter of them. “For example, in the 2019 federal election, the 157 MPs belonging to the Liberal Party were elected by only 3.7 million of the 17.9 million voters who participated in that election (20.8%). Even in the 2015 election, which returned a majority government, the 184 MPs belonging to the Liberal Party were elected by only 4.6 million of the 17.7 million voters who participated in that election (26.2%).”

This evidence will let us argue that our current voting system does not respect one of the core tenets of democracy - namely, that legislative decisions should be made by representatives elected by a majority of voters.

Thanks to Byron Weber Becker, we were able to process historical election data in Canada going back to our first election as a country in 1867. The figure below shows that it’s been a consistent feature of Canadian elections for our entire history that MPs from the winning party are elected by only about a quarter of the voters.

Percentage of effective votes (solid shades) and ‘wasted’ votes (lighter shades) cast for the party that won the greatest number of seats in each Canadian federal election.

We have also been able to show that “the winning party’s vote share (as received by all its candidates) has historically been going down” - even when counting just the elections resulting in majority governments, where the winning party’s candidates received a vote share “averaging 44.7% in the first four elections [of the past 40 years] resulting in a majority (1980, 1984, 1988, and 1993) and decreasing to an average of 39.6% in the last four resulting in a majority (1997, 2000, 2011, and 2015).”

Canada Has Moved Away From Principle of Majority Rule:

We concluded that, “overall, the typical result of Canadian federal elections under FPTP in recent decades is that candidates from the party that wins the most seats [only] win up to about 40% of the popular vote. Yet despite there having been only a single true majority government in the past 59 years (after the 1958 election) and despite having its MPs elected based on votes cast by little more than a quarter of the voters (typically cast in a limited portion of the country), the party winning the most seats nonetheless secures majority power in Parliament close to 70% of the time (~41 of the 59 years). This suggests that Canada has over the past few decades moved decisively away from the principle of “majority rule”.”

Stay tuned for more information!

Case Update & Introducing Fair Voting BC Evidence

As a follow-up to our last communication, we are still waiting for the government affidavits. It could be a few more weeks at this point, and we'll share any new updates as soon as possible. In the meantime, we're pleased to share more information from our case evidence.

Fair Voting BC Evidence

Over the past number of months, we’ve walked you through the evidence put forward by the four expert witnesses we invited to submit affidavits in this case: Profs. Nadia Urbinati (Columbia University), John Carey (Dartmouth College), Karen Bird (McMaster University) and Lawrence LeDuc (University of Toronto).

In addition to these experts, Antony Hodgson (president of Fair Voting BC and a professor at the University of British Columbia) also worked closely with some other experts (Byron Weber Becker (University of Waterloo) and Fred Cutler (University of British Columbia) to put together our own unique analyses to support our key contention that the First Past the Post voting system fails to effectively represent voters. In the coming few emails, we’ll share key insights.

Antony Hodgson (President, Fair Voting BC & University of British Columbia), Byron Weber Becker (University of Waterloo) and Fred Cutler (University of British Columbia).

The 2019 Canadian Federal Election

The first section of our affidavit reviews the results of Canada’s 2019 election in order to illustrate in our own national context some of the key problems described by the expert witnesses.

The first thing we pointed out was that “in a strong majority of ridings in the 2019 Canadian election (215 out of 338, or 63.6% of them), the winning candidate did not win a majority of votes. Many won significantly less. In particular, two candidates were elected with less than 30% of the votes cast in their ridings.”

While this is an interesting first point for the court to consider, we went on to make an even more important and central point by stating that it is important “to distinguish between votes cast for candidates who are elected and those that are not. We define a vote cast for an elected candidate as “effective”, as such a vote affects the composition of the legislature, and one cast for a candidate who is not elected as “ineffective”, as such votes do not have any effect on the composition of the legislature. Ineffective votes are commonly referred to as “wasted votes.””

“Of the 17.9 million voters who cast votes in 2019, a majority of over 9.1 million (51.0%) cast wasted votes.” This is the main fact that we plan to rely on in making our case - over half the voters do not have an MP they have voted for, and we will argue (based on Prof. Urbinati’s evidence) that this consequence of FPTP implies that these voters are not effectively represented.

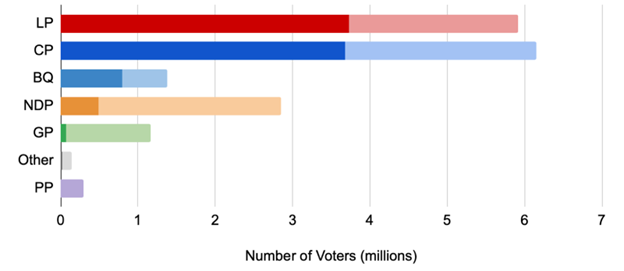

In addition, “There was a strong link between a voter’s political preferences and the likelihood of casting a wasted vote, with supporters of some parties affected to a greater extent than others. Large majorities of voters who voted for the NDP, the Green Party, the People’s Party of Canada, or for independent candidates in the last election cast a wasted vote” (as well as significant numbers of Liberal and Conservative voters - see figure below), which means that certain kinds of voters (“characterized by political preference and region”) are systematically discriminated against.

Representation of effective votes (solid shades) and ineffective, or wasted, votes (lighter shades) cast by party in the 2019 Canadian federal election. An effective vote is one cast for a winning candidate, while a wasted vote is one cast for a losing candidate.

In upcoming messages, we’ll dive deeper into the rest of the evidence we’ve put together.

Voices from the Movement - Event Recording

A big thank you to those who attended the Voices from the Movement Session, presented by Unlock Democracy Canada. If you were unable to attend or would like to revisit, a recording of the session is available here.

Final Thoughts from Prof. LeDuc

In our recent messages, we’ve shared with you much of the evidence Prof. Lawrence LeDuc presents about the negative effects of our First Past the Post voting system. In the final section of his affidavit, Prof. LeDuc summarizes Canada’s previous experiences with proportional voting and explains why, if it worked better than FPTP, we didn’t keep it and haven’t switched even more decisively to using it in all Canadian elections.

Canada’s Previous Experience With Proportional Voting

While it may be surprising to some, since all provincial and federal elections now use FPTP, Prof. LeDuc notes that “Canada has not always exclusively used FPTP in single member districts in the past. We have had multimember ridings at both the federal and provincial levels, and Alberta and Manitoba used STV [the Single Transferable Vote] in provincial elections in big cities between 1920 and 1955.”

Why We Haven’t Adopted Proportional Voting

But if proportional voting was used, why haven’t we stuck with it and even expanded its use? Prof. LeDuc points out that “in 1921, the first federal election widely contested by three political parties,” “an active debate at the federal level about FPTP began that year, and the issue has been debated more or less continually since that time.” Indeed, a Special Committee on Proportional Representation and the Subject of the Single Transferable or Preferential Vote was convened that year, though the politicians of the day declined to follow through on its recommendation that a public plebiscite be held.

Natural Conflict of Interest

LeDuc comments that “given the natural conflict of interest of governments with respect to reforming the very electoral system that elected them, partisanship and entrenched interests have combined to keep FPTP in place,” and indeed to repeal proportional voting where it was used. He goes on to review a number of other electoral reform initiatives at both the federal and provincial levels, noting that “because the electoral system sits at the root of partisan self interest, proposals for change were always linked in one way or another to partisan politics.”

Inconsistency

LeDuc also demonstrates politicians’ inconsistency by noting that “opposition parties often express support for reforms while they are in opposition, then lose interest in the same ideas when they are in government,” and citing Mackenzie King’s about-face in the 1920s as the first significant example.

Partisan Self-Interest

He calls further attention to politicians’ self-interest when he says that “Governments typically see proposals for institutional change either as threats to their position or as opportunities to advance a partisan agenda. In the former case, proposals that are put forward by organizations or groups outside of government are easily ignored or sidelined.” And “when governments do decide to act on a reform proposal, they often do so from a perspective of gaining a political advantage over their opponents,” and not because of any principled commitment to the best interests of voters.

We feel that this evidence of strong self-interest and partisan self-dealing on the part of politicians will help us convince the courts that they shouldn’t automatically defer to governments on this issue and should provide appropriate direction to them.

Thank you for your continued support. More on the other affidavits coming soon!

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC

Negative Effects

We’ve recently shared with you some of Prof. Lawrence LeDuc‘s evidence that our First Past the Post voting system has deeply negative consequences for both individual voters and for the country as a whole.

FPTP Makes Unhappy Voters

Later in his affidavit, Prof. LeDucRecent points to how important it is for voters to gain parliamentary representation when they cast their vote in an election: “experimental research demonstrates clearly that voters do care about the degree to which their votes are reflected in the distribution of parliamentary seats, and that this affects their degree of satisfaction with electoral institutions and with the perceived fairness of the political system more generally.” He presents evidence that “only about half (54%) of Canadians … were “very satisfied” or “fairly satisfied” with “the way that democracy works in this country”,” compared with much higher levels “in Denmark (92%,) Sweden (80%), or The Netherlands (78%) – all PR countries.” “The electoral system was among the most frequently-mentioned reasons [for their dissatisfaction] – second only to the concentration of power in the executive, which is itself a function of our FPTP electoral system,” and notes that “should Canada change to a PR system, it is likely that the level of satisfaction with the political system would increase.”

Negative Effects on Younger Voters

Prof. LeDuc’s evidence clearly supports Prof. Karen Bird’s findings (which we described recently) that FPTP leads to under-representation of women and minority groups, and adds evidence that “young voters, whose issues and concerns differ from those of older voters, ... are typically under-represented as MPs in Parliament under the existing FPTP system. This divergence has, in recent years, contributed to declining turnout among younger age groups.”

A Host of Other Negative Effects

Prof. LeDuc outlines a host of other negative effects of FPTP voting in the Canadian context:

Low voter turnout: “Research has consistently found that one of the reasons for declining turnout in Canada is the feeling among citizens that their votes too often do not really count under the present system, or that the choices presented to them in many constituencies are inadequate.”

Strategic voting: “Canadian voters hate the idea of strategic voting – effectively being told to vote for a candidate that they don’t want in order to prevent a candidate that they like even less from being elected. Rather than encouraging participation, this configuration more often prompts withdrawal.”

Safe seats: ““Safe” seats lead to increased voter dissatisfaction and higher rates of withdrawal from voting.” “In “swing” ridings, on the other hand, turnout tends to be higher, because voters feel that their votes matter and they have the chance to impact the election of a representative. The concepts of “safe” and “swing” ridings have no meaning under PR.”

We feel that all of these issues are highly relevant to the claim we’ll be making in our arguments that our voting system does not deliver effective representation, as required by our Charter.

Wishing you a lovely and safe holiday season! Thanks for all of your tremendous support this past year.

Jesse Hitchcock, Springtide & Antony Hodgson, Fair Voting BC